A European Parliament mission of five cross-group members visited Germany on 3 and 4 November 2022. The purpose of the mission was to assess the functioning of the German Youth Welfare Offices, generically called Jugendamt, after new citizen claims had been filed on the matter before the parliamentary Committee for Petitions (PETI).

The need for control over the Jugendamt is not new. As early as 22 March 2007, a first visit of parliament members to the German Youth Welfare Offices had already taken place. More recently, the European Parliament had issued a 29 November 2018 resolution on the role of the Jugendamt. The report of the current visit states that not all parliamentary recommendations agreed five years ago have been implemented to this date.

In particular, the European Parliament stresses once more the need to increase transparency of the German Youth Welfare Offices, through the collection of statistical data. Indeed, the representatives of the Jugendamt failed to provide objective data in response to several questions posed by different MEPs during the mission.

For instance, to an inquiry submitted by MEP Dolors Montserrat, Head of Mission on custody given to parents, Ms. Cornelia Lange, Head of the Family Department in the Hessen Ministry on Social Affairs and Integration, responded that she had no statistics which she could provide.

To a similar question asked by German MEP Peter Jahr on whether “foster families can earn a lot of money when accepting children”, Ms. Lange replied that, concerning funds, “it is about municipal means in the context of municipal duties”. Thus, she eluded the matter referring to the fact that the Jugendamt offices are part of municipal government and therefore difficult to control by the German federate states.

MEP Marc Angel also submitted a financial request to Ms. Lange, namely, if the Jugendamt sends invoices for care to parents. The German civil servant did recognise that if parents dispose of a certain level of financial income, it can be expected from the parents to participate in the costs for care. However, she did not specify accurately what she meant by “certain” and by “participate”.

When MEP Tatjana Ždanoka asked about the ratio between children put into foster families versus municipal establishments, Ms. Katrin Hombach, Deputy Head of the Foster child care, adoption and family law in the said Hessen Ministry, replied that this depended on the age of the children, with children aged between 0-6 years living mostly with foster families and older children staying more often in facilities. This data was later challenged by Ms. Esther Wagner, Head of Social Services in the Wiesbaden Jugendamt, who placed the age border at 12 years rather than 6.

Concerning the relationship between courts and the Jugendamt, MEP Jahr asked who is controlling said administrative body; similarly, MEP Kosma Złotowsky recalled that, according to the various complaints that PETI had received, the German courts “always follow the opinion of the Jugendamt”. Dr. Katja Schweppe, judge at the Higher Regional Court of Frankfurt am Main, replied that she could not speak for her colleagues.

MEP Angel asked about legal fees aid for parents with a lower income who need to go through procedures in family matters. Ms. Annell Zubrod, Deputy Director of Administration of Justice in the Hessen Ministry of Justice, stated that she did not know the exact numbers.

When MEP Ždanoka told representatives of the Frankfurt Jugendamt that, according to petitioners’ claim since years, the German Youth Welfare Office “mostly positions itself in favour of German citizens” in cross-border issues, Ms. Erika Dannhäuser, Officer of the Child and Welfare Unit replied that she did not know any statistical data that could refute the statements of individual petitioners.

Along the mission it became quite clear that the role and action of said offices are often seen as too far-reaching, because Germany’s child and youth policy transfers a big responsibility and power to the Jugendamt. Ms. Daniela Leß, Head of the Wiesbaden Jugendamt, recognised that children had even been taken “200 km or more” away from their home. Additionally, it is very rare that children taken into custody by the Jugendamt can return to their parents.

However, Ms. Lange explained that Jugendamt can only take children into custody when they are in “inminent danger”. Mr. Erhard Meier, judge for family affairs in the Family Court of Wiesbaden, explained that situations of danger include preventing children from dying out of hunger or from freezing to death, as well as from sexual abuse.

For all these reasons, Head of Mission Montserrat qualified the Jugendamt as a “shadowy body”. She further commented that “where there’s smoke there’s fire”, based on the high number of complaints received by the European Parliament on the German Youth Welfare Offices implying frequent accusations against the member state’s system.

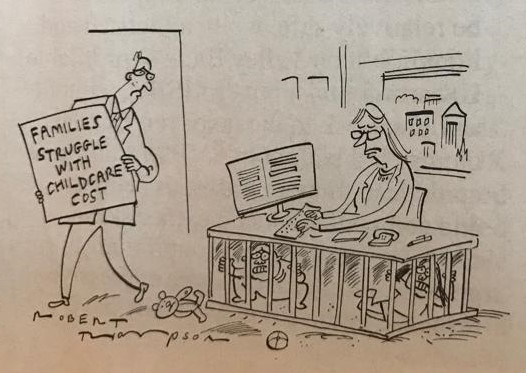

Source of image: The Spectator, 18 March 2023

Subscribe

Subscribe