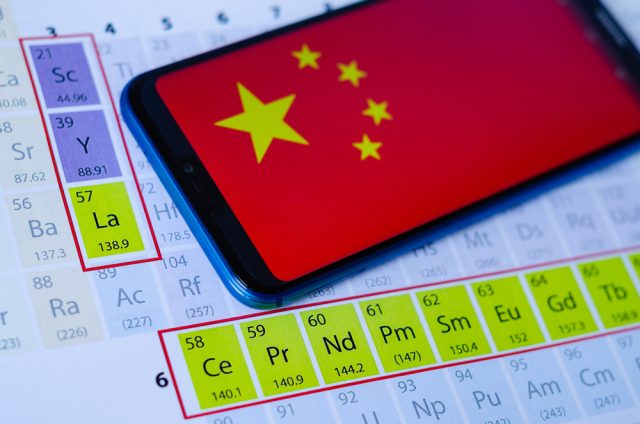

The European Union’s demand for rare earths will increase fivefold by 2030. These are metals, minerals and other materials that are now part of our daily lives. Lithium, Cobalt and all those raw materials needed to make batteries for electric vehicles, wind turbines and solar panels are becoming crucial to sustain the new industrial ecosystem.

To these must be added many other elements such as tungsten, gallium and indium, which are essential for the functioning of mobile phones, LEDs and various everyday devices.

The European Green Deal depends on the supply of these resources, which are about to become much more important than oil and gas, as recently stated by EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in announcing a legislative initiative called the Eu Critical Raw Materials ACT.

The problem is that for now, the European Union is largely dependent on autocratic regimes such as China for the supply of these raw materials. Suffice it to say that the regime led by the Chinese Communist Party owns 98% of the rare earth supplies destined for European needs. This enormous dependence undermines the foundations of Europe’s ambition to achieve the Green Deal on schedule, but above all, without having to suffer blackmail from autocratic powers, as in the case of the war in Ukraine and dependence on Russian gas.

Breaking free from this subordination to unwelcome suppliers is not easy. China has been in the commodities market since the 1980s with a strategy that has diversified over the years in order to occupy production slots abroad as well, so as to secure the extraction of precious minerals in Africa for instance, where the People’s Republic – but also Russia – has a well-established and ever-expanding capacity for meddling.

The EU’s autonomy in accessing the resources necessary for the transition from fossil fuels to alternative and renewable energies is a strategic security issue that can no longer be postponed; indeed, the lesson of Russian gas shows that Europe is already guilty of lagging behind on this dossier.

The ECR Group has already warned in the past about the risks of dependence on the Chinese dragon, which in recent years has already applied blackmail policies on supplies of rare earths and other mineral materials to some non-European ‘partners’. This is why, about a year ago, the Conservatives presented ECR rapporteur Anna Fotyga’s own-initiative report on the Arctic. The aim is to maintain peaceful cooperation in a region that – targeted by Russian interests – in the framework described so far can and should be one of the possible solutions to the problems of raw material hoarding.

The Arctic region’s potential for rare earths is strategic, but one has to reckon with the climate and the relative conditions of those territories, furthermore, the indigenous peoples are reluctant to let their habitat be exploited for industrial purposes, while the whole area is increasingly becoming the centre of international tensions in the global challenge for finding critical raw materials.

The EU Commission has become increasingly aware of the strategic risks the Union faces in this area.

In 2020, it launched the ‘Action Plan on Critical Raw Materials‘ with the intention of planning the necessary actions to support the Green Deal and the EU Industrial Strategy precisely in the area of raw material sourcing as a strategic independence.

The plan outlines the challenges for Europe and the ten actions identified as necessary to achieve ‘reliable, secure and sustainable access to raw materials’ as a prerequisite for the European Green Deal and Europe’s industrial leadership in the technologies of the future.

The actions listed in the plan include both secondary recovery projects for the minerals so necessary for the European economy, and the identification of actual extraction and processing projects for raw materials within the EU. This is a particularly critical point for the widespread environmental awareness of a large part of European citizens. According to warnings issued by environmentalists, opening new mines risks creating unsustainable disruptions to the environment of the territories concerned, endangering human and animal health, undermining biodiversity and polluting groundwater.

Therefore, pressure is mounting from environmental groups to focus EU policy on secondary recovery, by recycling waste and extracting from it the rare earths that are present and no longer used.

At the same time, the Commission is working to ensure that projects to open new mines on European soil can benefit from simplified authorisation procedures and private investment to accelerate the achievement of the independence targets set in the plan. How this policy can be reconciled with the promises of environmental sustainability can only be explained by an acknowledgement of the need for a fair trade-off between the values the EU strives for and the strategic needs to be met with a massive dose of realpolitik.

Against this backdrop, the Action Plan on Critical Raw Materials envisaged the formation of the industry-led European Raw Materials Alliance (ERMA).

The Alliance aims “to make Europe more economically resilient by diversifying its supply chains, creating jobs, attracting investment in the raw materials value chain, fostering innovation, training young talent and contributing to the best framework for raw materials and the circular economy worldwide.”

The challenge is to increase the production of raw materials in a sustainable manner by 2030 by promoting projects that have recycling of critical raw materials at their core. We are talking about ambitious targets because they concern the setting up of a circular economy process concerning the recovery from complex products such as electric vehicles, clean energy technologies and all those products of modern industry that already use rare earths that should be extracted to minimise the impact created by mining from scratch.

An ambitious challenge, but also a race against time as independence from China can no longer be postponed.

Hence von der Leyen’s announcement a few weeks ago in her State of the Union address: the European Critical Materials Act.

On 30 September, the Commission kicked off the public consultations on the law, these will last until 25 November, then it will be the turn of the drafting of the proposed regulation to be drawn up and approved by the first quarter of 2023.

The conclusion of the process should lead to a regulation based on three strategies focusing on the critical issues and opportunities described so far. The search for new foreign partnerships in raw material supply, forging exchange relationships with countries that share the same EU values; urban mining understood as the process of recovering and recycling rare earths from technologies within the framework of a circular economy; and the expansion of this more environmentally sustainable recycling capacity in the long term.

In the background are global tensions and the competition between superpowers in the hunt for precious minerals for the civil and war industry of the present and future, with increasingly worrying levels of souring international relations. Europe can no longer be found unprepared and weakened in this high-risk scenario for the security of the entire bloc. Especially with regard to the creation of new extraction plants, which are already taking a long time from an industrial point of view, in addition to the interference of NGOs, environmentalist pressure groups and civic committees of the territories concerned that are legitimately concerned, but as we said, a compromise must absolutely be found. Doing it soon is imperative.

Subscribe

Subscribe