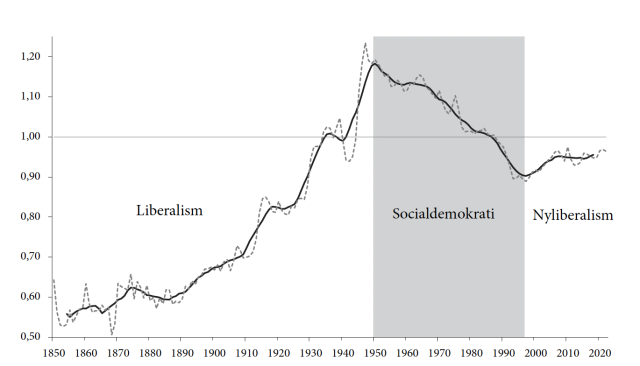

Both Nobel Laureate Paul Samuelson and the well-known American economist Jeffrey Sachs have used Sweden as an example of successful social democracy, illustrating the feasibility and, indeed, desirability of the middle way. In a recent paper, Swedish economist Lars Jonung offers a markedly different interpretation of the Swedish story. He distinguishes between three Swedish models: liberal in 1870–1950, social democratic in 1950–2000, and neoliberal since 2000. In the liberal period, Sweden experienced rapid economic growth, her average income (GDP per capita) increasing from 60 per cent of the average income in fifteen comparable countries to 120 per cent. In the social democratic period, however, she began to lag behind these countries, her average income decreasing to 90 per cent of their average income. In the third period, Sweden recovered somewhat, but she has not yet caught up fully with these countries of reference. Jonung’s results are shown in the chart above, where the broken line represents the data of each year while the continuous line represents a nine-year average.

Comparative Economic Growth

Jonung’s results show not how Sweden has been performing on her own, but, more importantly, how she has been performing in comparison to the fifteen countries of reference. They are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, Germany, and the United States. The results are stable: it makes no difference whether Sweden is compared with the five large countries in the group or with the ten smaller countries. Jonung uses the data set on GDP per capita, adjusted for purchasing power parity, compiled by Angus Maddison and updated by researchers at the University of Groningen. Moreover, in his paper Jonung offers a plausible explanation in terms of institutions and incentives for the differences between the three periods.

The Liberal Model, 1870–1950

In the mid-nineteenth century and onwards, the Swedish economy was greatly liberalised. The guild system was eliminated, restrictions on mobility and several regulations in agriculture were abolished, private property rights strengthened, and tariffs reduced or scrapped. It was, Jonung holds, of particular importance that in 1855 financial institutions were allowed to set interest rates freely and that soon thereafter a stock market was established. A competitive capital market emerged, encouraging innovation. Despite the reintroduction of some tariffs in late nineteenth century, the economy remained largely open. In the mid-1930s, the Swedish economy had caught up with the economies of comparable countries. When the Social Democrats came to power in 1932, Sweden was already one of the world’s most prosperous countries.

The Social Democratic Model, 1950–2000

During the Second World War, currency and rent controls were introduced, and the Social Democrats, in power continuously from 1932 to 1976, retained them thereafter. They also sought to regulate the capital market, directing investment away from private initiatives. One effect was that the total value of stocks, as a proportion of GDP, declined. Another effect was that newcomers, entrepreneurs and innovators, found it difficult to compete for capital with the already established firms and with public institutions. From the 1950s to the late 1990s, the number of public employees increased significantly, whereas no new jobs were created in the private sector. The economy stagnated.

The Neoliberal Model, 2000–2020

Slowly, and after heated discussions, the Swedes began to retreat from the social democratic model. Jonung ascribes much importance to two kinds of financial deregulation: in 1985 credit limits imposed on private banks were removed; and in 1989 currency controls were abolished. Taxes became less progressive. The non-socialist coalition government under Carl Bildt in 1991–1993 introduced competition in various sectors previously dominated by public institutions. It abolished the government monopoly of broadcasting, allowed the currency to float, and abolished the so-called wage-earner funds, which had been designed to transfer control of the economy to the trade unions. The reforms continued thereafter, both under Social Democrats and coalitions of the non-socialist parties. The tax burden was eased somewhat, and public companies were privatised. Although special interests retain some privileges, the reforms have led to renewed economic growth. Samuelson and Sachs were proven wrong. The lesson to be learned from Sweden is: Freedom works.

Subscribe

Subscribe