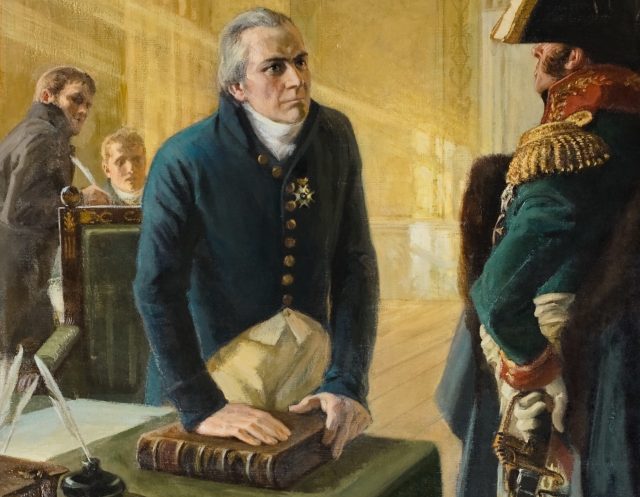

In these turbulent times, the Nordic countries, not least Finland, stand out as examples of liberty, prosperity, and stability. Consider Finland, which I have, as an Icelander, long admired from afar. There, courthouses are usually adorned with reproductions of a famous painting (above) by Albert Edelfelt. It depicts a scene from Johan Ludvig Runeberg’s epic poem The Songs of Ensign Stål, set during the 1808–1809 war between Russia and the Kingdom of Sweden, which at the time encompassed Finland. The Commander of the victorious Russian forces, Count von Buxhoevden, demands that a local governor in Finland, Olof Wibelius, confiscate the property of defiant Swedish officers. The governor, with his hand on the 1734 Swedish-Finnish lawbook, refuses, as doing so would violate the law. Ultimately, the Russian general relents. While the poet and the painter took some liberties with what actually happened (the Russian general and the Finnish governor corresponded but did not meet in person), the scene illustrates the strong tradition of liberty under the law, common to all the Nordic countries. This tradition had been articulated in 1765 by the Finnish pastor Anders Chydenius in several remarkable pamphlets, anticipating both Adam Smith on economic freedom and John Stuart Mill on freedom of the press.

Finland a Pioneer of Democracy

Although Finland was under Russian rule after 1809, as a Grand Duchy of the Tsar, she remained a Nordic country, cherishing her common heritage with Sweden. Initially, the Tsar allowed her to retain her law, her two languages, Finnish and Swedish, and her Diet of the Four Estates, of the nobility, clergy, burghers, and farmers. In late nineteenth century, however, the Tsar started a Russification campaign. He had to retreat after the Russian defeat in the 1904–1905 war against Japan, and in 1905, the leader of the passive resistance to Russification, Leo Mechelin, became prime minister. As professor of law at the University of Helsinki, Mechelin had argued that Finland was a separate state, not a Russian province with special status. As prime minister, he introduced general suffrage, restricted only by age, not by sex or income. Indeed, Finland was the first European country to extend the vote to women.

Four Wars Against Totalitarianism

In late 1917, after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, Finland declared her independence. A liberal constitution, drafted by the conservative-liberal scholar Kaarlo Ståhlberg, was adopted, and Ståhlberg became the country’s first president. But subsequently, Finland had four times to defend herself against the totalitarians, first against a socialist rebellion in 1918, then against Russia in 1939–1940 (the Winter War), and in 1941–1944 (the Continuation War), and finally against the German Nazis in 1944 (the Lapland War). In all four wars, the Finnish military forces were ably led by Baron Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, who deservedly became a national hero. In his last Order of the Day in the Winter War, on 14 March 1940, Mannerheim stated that the Finns were proud to have defended Western civilisation. Referring to a poem by Zacharias Topelius on the debt the Finns owed to Swedish culture, he added that they had now paid that debt in full.

An Outpost of Western Civilisation

The idea of Finland as an outpost of Western civilisation was also expressed in a well-known poem by Uuno Kailas:

The border opens like a chasm.

Before me Asia, the East,

Behind me Europe, the West

which I, the sentry, guard.

Mannerheim was the embodiment of two typical Finnish traits: the courage to fight when inevitable and the willingness to compromise when necessary. He needed the first trait for his heroic performance in the Winter War, when the Finns rendered to the other Nordic countries the same service that the British rendered to Europe in the Second World War, standing up to totalitarianism. Then, Mannerheim was Finland’s president in 1944–1946 when his nation, in a precarious situation, certainly needed the second trait, the willingness to compromise. Mannerheim was no scholar, but, interestingly, in his memoirs, he invoked the example of Switzerland as a well-governed country, not least, I would suggest, because the Swiss coped successfully with the same problem as the Finns: the nation spoke more than one language. But in the 108 years since their independence, the Finns have amply demonstrated that they are a Nordic nation.

Subscribe

Subscribe