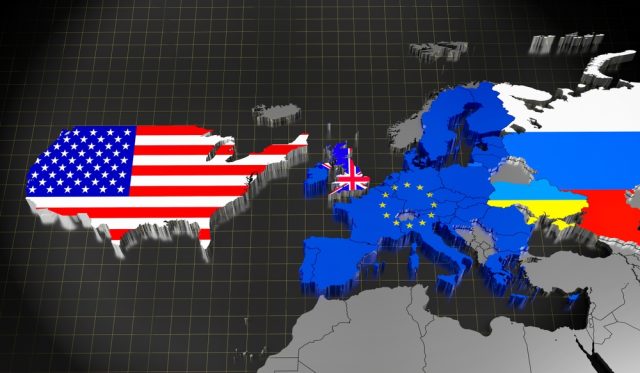

The publication of the 2026 U.S. National Defense Strategy (NDS) marks a turning point not only for American military planning, but for the entire transatlantic system. This is not a technical document, nor a routine update. It is a political-strategic statement that sets out priorities, hierarchies, and limits.

For Europe, the message is unambiguous: the age of strategic ambiguity is over. For decades, European security has rested on a tacit assumption—that American commitment was permanent, elastic, and largely unconditional. The new NDS does not break the Atlantic bond, but it redefines roles. Washington is not withdrawing; it is clarifying expectations.

This clarification forces Europe to confront a question it has postponed for too long: is it willing to take primary responsibility for its own security?

The American shift: priorities and realism

Homeland first

The cornerstone of the new U.S. strategy is the primacy of homeland defense. Borders, airspace, maritime approaches, cyber resilience, and nuclear deterrence are explicitly identified as the top priority. This reflects a broader return to strategic realism: security begins at home, not in abstract global management.

Indo-Pacific centrality

The second pillar is the Indo-Pacific, with China identified as the main long-term strategic competitor. The NDS frames Beijing neither as an inevitable enemy nor as a partner to be accommodated, but as a power whose growing military capabilities must be deterred through strength, not confrontation.

This prioritisation has a direct implication for Europe: U.S. strategic bandwidth is finite. Resources, attention, and military assets cannot be everywhere at once.

Europe and NATO: allies, not dependents

The NDS reaffirms America’s commitment to NATO, but it does so in a new tone. The alliance remains vital, yet its internal balance must change.

The document is explicit: European allies must assume primary responsibility for conventional defence on the continent, with the United States providing critical—but limited—support. This is not presented as punishment, but as strategic necessity.

Most striking is the elevation of burden-sharing to a structural principle. The NDS references a new benchmark agreed within NATO: 5% of GDP dedicated to defence and security, combining 3.5% for core military spending and 1.5% for related security investments. This is no longer a symbolic target; it is framed as the baseline for credible deterrence.

The “simultaneity problem”: a stress test for Europe

One of the most important analytical concepts in the NDS is the “simultaneity problem”—the risk that multiple adversaries could act concurrently across different theatres.

For the United States, this reinforces the need to prioritise. For Europe, it exposes a vulnerability: automatic American availability can no longer be assumed.

The irony is evident. The combined economic weight of non-U.S. NATO members far exceeds that of Russia. Yet economic potential has not translated into military readiness, operational cohesion, or industrial capacity. The problem is not resources, but organisation, will, and strategic culture.

Europe’s real weaknesses—beyond rhetoric

Fragmented spending

European defence spending remains fragmented across national lines, producing duplication rather than strength. Multiple weapons systems, incompatible standards, and parallel procurement programmes undermine effectiveness.

An underpowered defence industry

Europe’s defence industrial base suffers from slow production cycles, technological dependencies, and regulatory obstacles. While political declarations on “strategic autonomy” multiply, actual industrial output remains insufficient to sustain prolonged high-intensity conflict.

Political confusion

Perhaps the most serious weakness is conceptual. “European defence” is too often framed as an ideological project rather than a strategic necessity. This has led to confusion between security cooperation and political centralisation, alienating national governments without delivering real capabilities.

What Washington is not asking Europe to do

It is crucial to clarify what the NDS does not demand.

It does not call for:

- A supranational European army

- The erosion of national sovereignty

- A break with NATO

- An anti-American “strategic autonomy”

On the contrary, the American message is pragmatic: stronger states make stronger alliances. What Washington wants are reliable partners, not bureaucratic constructs.

The necessary European posture: conservative realism

A credible European response must be grounded in realism, not illusion.

Defence is a core function of the nation-state, not a symbolic policy area. Cooperation should be intergovernmental, capability-driven, and focused on outcomes. Industrial policy must treat defence as a strategic asset, not a regulatory afterthought.

This approach aligns fully with conservative principles long upheld within the ECR tradition:

- National sovereignty as a foundation, not an obstacle

- Subsidiarity over centralisation

- Responsibility instead of dependency

- Security as the precondition of liberty

A Europe that cannot defend itself cannot meaningfully protect its citizens, its borders, or its democratic institutions.

Maturity over illusion

The 2026 U.S. National Defense Strategy does not diminish Europe. It challenges it to grow up.

The real danger is not higher defence spending, nor greater responsibility. The real danger is continuing to pretend that strategic protection can be outsourced indefinitely.

In a world of returning power politics, credibility matters. An undefended Europe is not a partner—it is a strategic liability. The choice is no longer theoretical. It is political, immediate, and unavoidable.

Subscribe

Subscribe