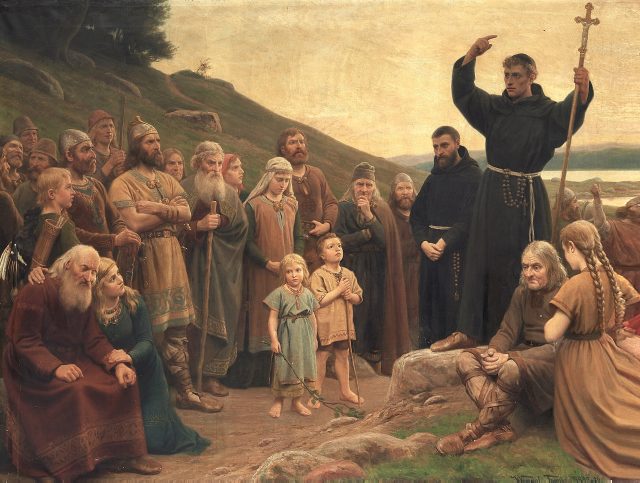

In his Germania, written in 98 AD, Roman chronicler Tacitus described German self-rule through assemblies, where disputes were settled, lawbreakers convicted, kings selected (and deposed), and, most importantly, the law was defined and revised. For example, in 852, the missionary Ansgar, Bishop of Hamburg, returned to Sweden after an earlier trip. He was told by the Swedish king, Olof, that in his country the control of public business rested with the whole people and not with the king. Accordingly, Ansgar sought and received permission from an assembly to preach, as depicted in the painting above by Wenzel Tornøe. Indeed, the Swedes can pride themselves on a long tradition of limited government and representative democracy. The kings were under the law like the rest of the population, and they had to seek the consent of popular assemblies for all major decisions.

Peasant Democracy

Another example of this Germanic tradition is a speech by Swedish Lawman Torgny at a regional assembly in 1018. King Olof of Sweden was hostile to his namesake, King Olav of Norway. But if he were to wage war on Norway, Torgny said, the farmers would kill him. He recalled that some previous kings had been killed for lawlessness and arrogance. King Olof immediately retreated. When the Swedes elected a king at a meeting in 1319, they adopted a charter limiting his power: no new taxes were to be levied without the agreement of the people, and no man could be punished unless he had broken the law. In 1397, however, the Danish monarch acquired the Swedish crown. But Danish rule was unpopular, and in 1434 a mine owner, Engelbrekt Engelbrektsson, led a rebellion against the Danes. In 1435, at a meeting in Arboga, he was elected Leader of the Realm. This is traditionally considered the first meeting of the Swedish Riksdag, a Diet of four Estates: the nobility, the clergy, the burghers, and the farmers. Sweden was the only European country where farmers were represented in parliament (although in Norway and Switzerland, they also had some representatives in popular assemblies). Engelbrekt was, however, soon killed.

Liberalisation in Sweden

After Sweden regained independence in 1523, the kings sought to expand their powers. They imposed absolutism in 1680, although the Diet of the Four Estates continued to exist. But when Sweden was defeated in the Great Northern War of 1700–1721, the monarch had to transfer significant powers to the Parliament, where two parties formed, similar to the Whigs and Tories in England. Under the influence of a Finnish delegate to the Estate of the Clergy, Anders Chydenius, Sweden in 1765 adopted a Freedom of Information Act, the first of its kind in Europe. She also abolished some trade monopolies. In 1809, an authoritarian king was deposed in a rebellion led by Count Georg Adlersparre, who had translated parts of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations into Swedish. Adlersparre was probably the first to use the word ‘liberal’ about his views. But it was Baron Johan August Gripenstedt, government minister in 1848–1866 and an ardent disciple of the French free trader Frédéric Bastiat, who transformed the Swedish economy by a comprehensive liberalisation programme. Consequently, between 1870 and 1930, Sweden became one of the wealthiest countries in the world.

A Strong Tradition

In the early twentieth century, two world-famous Swedish economists, Gustav Cassel and Eli F. Heckscher, became eloquent and effective critics of socialism. It was not least because of their influence that the Social Democrats, who took power in 1932 and ruled continuously until 1976, had to retreat from their most extreme positions. In the last decades of the twentieth century, Sweden’s long tradition of liberty was reinforced, both in theory and practice. It well demonstrates its strength, its deep roots, that it withstood both the onslaught of kings claiming to reign by the grace of God, and that of social democrats, claiming to rule in the name of the People. Sweden should be an inspiration, not to social democrats, but to conservatives and liberals alike.

Subscribe

Subscribe