Is it a strength not to be afraid? Is it a strength not to be hindered by religion, traditions and belief in authority? Yes, sometimes it may be. Even conservative people should be able to admit that. Fearlessness can be good. Freedom can be good. Forward thinking can be good. But all of this can also be problematic.

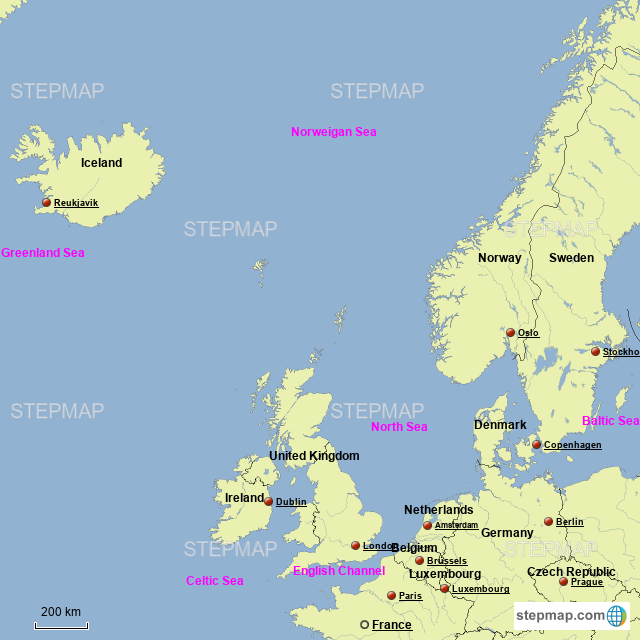

On the cultural map produced by the research network World Values Survey, we find the cultural sphere called “Protestant Europe” at the top right of the map. Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Finland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany are included in the European Protestant cultural sphere. Great Britain falls into the sphere called “English-speaking countries” and is closest to the more extreme Protestant Europe. Austria is located just on the other side in the sphere called “Catholic Europe” and where we also find large EU countries such as France, Spain, Italy and Poland.

And if we look at how the different countries in the cultural sphere of Protestant Europe rank in relation to each other, we see that Sweden is the country that ends up farthest up on the right. Sweden, a country that many see as a pioneer of secular values, individualism and belief in rationality, is therefore a country that stands out. It is true that the other Nordic countries rank quite close, but it is still a fact that Sweden stands out.

The cultural map is a diagram. On the vertical y-axis, the attitude towards traditionalism versus rationality and freedom is measured. Countries that are low on the map and therefore low on the scale where belief in traditions gives a low value and belief in pure rationality gives a high value are therefore countries where religion, authorities and history have a large role to play in society in general. On this scale, countries in the Confucian cultural sphere rank higher than the countries that are part of the European Protestant one. Japan and South Korea are thus said to have gone further than Sweden and Germany when it comes to freeing, for example, political decisions from belief in authority and loyalty to traditions.

The horizontal x-axis measures the attitude we have as individuals towards our own individual lives. Do we focus on survival or on self-realization? If we live to survive, we will be cautious, we will adapt to norms, we will protect ourselves from dangers, we will be skeptical of changes whose consequences we cannot foresee. We will also not have much energy left to transform ourselves into something we want to realize. We do not have much trust in life. Existence is dangerous and we must be on our guard against everything that threatens our safety. If, on the other hand, we focus on self-realization, we will devote energy to goal fulfillment, change, and work on change. We will not waste energy on protecting ourselves from everything that is dangerous because the world is not so dangerous. We therefore have trust in the world. It leaves us alone. It does not wish us harm. We have trust in other people, and we have trust in our own ability to realize ourselves in the way we ourselves desire.

Protestant Europe’s belief in progress and change has been beneficial. If we also include the English-speaking world, whose cultural sphere is right next to the Protestant one, many of the values that characterize the modern world and modern Europe come from these cultural spheres. We needed to leave traditions and authority behind to some extent to build the modern world with democracy and widespread prosperity.

But when we now see a conservative reaction worldwide to a progressive age that may have pushed its political theses a little too far, then with the help of the World Values System we can understand what can be perceived as weaknesses in progressive thinking.

And as good conservatives, we can start from the concept of balance. Aristotle already spoke of the golden mean. In his famous book The Nicomachean Ethics, he wrote that the middle way between two extremes is always praiseworthy. And that is how Europe and the West in general should think now. We have drifted too far in traditional criticism and individualistic self-realization and need to find a way back to a more nuanced position.

If we take the question of the values that should dominate in a society (that is, the values that are measured vertically in the World Values System diagram), it is obvious that we Europeans do not want to go back to our own Middle Ages. We allow ourselves to be critical of immigrant groups that cannot accept our modern freedoms and rights. We allow ourselves to believe in religious freedom, in the right to criticize religion, in the right of young women to decide for themselves who they will live with. There is a clear difference between our European cultural spheres and the cultural sphere called the “Afro-Muslim” one, which is located on the opposite side of the cultural map: at the bottom left.

But does that mean we should have no traditions left? Does that mean there should be no religious, moral or political authorities? Does that mean we should throw our Christian heritage overboard? Of course not. Because if we do that, we will destroy our own culture. And that is exactly what we have seen in Europe, and in the West in general, over the past thirty years. In the name of an authority-free universalism that only refers to universally valid human values that everyone is expected to embrace regardless of where people come from, we have thought that Europe can be just as “multicultural” as it can be “Western”. But it is not that simple. Europeans are also human. Westerners also need traditions and mysticism. Westerners also need history and a historically connected identity. Otherwise, we will be nothing.

And if we look at the question of our attitudes to life as individuals, it is also obvious that we have gone too far in believing that life only consists of wonderful self-realization. Being human is also being part of a context (hopefully), being part of something bigger than yourself, feeling that you are doing something useful for others, feeling calm and secure. Many Europeans, for example, have forgotten what it feels like to have war in your vicinity. Russia’s full-scale attack on Ukraine was a shock to many Europeans. Could it happen in our vicinity? Can a person (Putin) be so brutal that he demands the submission of an entire population? Can we all be subjected to this seemingly pure evil? Suddenly, it was necessary to think about the survival of oneself and one’s family. Suddenly, it was necessary to see oneself as a citizen of a country that guarantees my safety. Suddenly, many had something more down-to-earth to think about than their own self-realization.

Of course, war is not good. It would be wonderful if we could all just devote ourselves to realizing ourselves, but that is not how reality looks. Perhaps it is because we have lost touch with a complex and in many ways dangerous reality that we believe we can afford to devote ourselves only to self-realization. Here, real and dangerous conflicts can remind us that reality is not a pleasant novel and that we all also must think about our survival.

So, a little more balance perhaps. A little more of both individualism and traditionalism. It would probably be good for Protestant Europe, and for other parts of Europe if we moved a little closer to the center of the map. We do not need to be so extreme. WE must combine our optimism, our modernism and our individualism with reasonable conservatism and a healthy caution. It concerns our ability to defend ourselves militarily. It concerns our view of extensive and uncontrolled migrations. It concerns our view of morality and tradition. A strong Europe needs to be a balanced Europe. Nobody benefits from being extreme.

Subscribe

Subscribe