In recent decades, humanity has entered an era of accelerated transformation, driven by the confluence of technological progress, globalization, and, perhaps most importantly, climate change. Among the most controversial and fascinating phenomena being discussed by the governments of many world economic powers is the gradual reopening of the Arctic as a navigable space for transporting goods from Asia to Europe or to the east coast of the United States. Although researchers and environmental activists have been warning for many years that the melting of the ice caps should be seen as an unprecedented ecological wake-up call, this phenomenon, which has a major impact on the entire planet, also offers economic and geopolitical opportunities. The way in which trade routes through the Arctic Ocean are becoming part of a global puzzle of economic exchanges may be an answer to the essential questions about how dependent Europe is on China, both in terms of the overall picture of the transformations that maritime and air transport are currently bringing about. In this geopolitical context, we are also compelled to discuss a brief analysis of The New Golden Road – Europe to India map, a land-based alternative for the exchange of goods between Europe and Asia, as an overview of the possibility of diversifying the trade corridors that shape the future of globalization.

Global warming and the opening of the Arctic to maritime transport

Currently, one of the greatest challenges facing modern civilization is the issue of global warming. Average annual temperatures, which have risen significantly in recent decades, are causing Arctic ice to melt at an accelerated rate. According to studies conducted by specialists in the field, the Arctic region is warming three to four times faster than the rest of the planet. This reality, which cannot be ignored, has multiple implications. On the one hand, it heralds an ecological catastrophe that could result in the disappearance of natural habitats, the loss of biodiversity, and threats to indigenous communities. On the other hand, it opens up unexpected economic prospects for access to new trade routes that would shorten travel times and operating costs on the Asian-European-American route. With the melting of the glaciers, maritime transport through the Arctic is becoming a real possibility, even if it is still limited.

A first fundamental question would be whether we can talk specifically about opening transport routes through the Arctic. Yes, it is possible to envisage the future of maritime transport through the Arctic, but it remains dependent on infrastructure (here we are talking about ports), a specialized fleet (shipping vessels capable of crossing the Arctic Ocean among ice floes) and political will (a genuine trade agreement between the US, the Russian Federation, the European Union and China, the main decision-makers).

The possibility of maritime transport through the Arctic

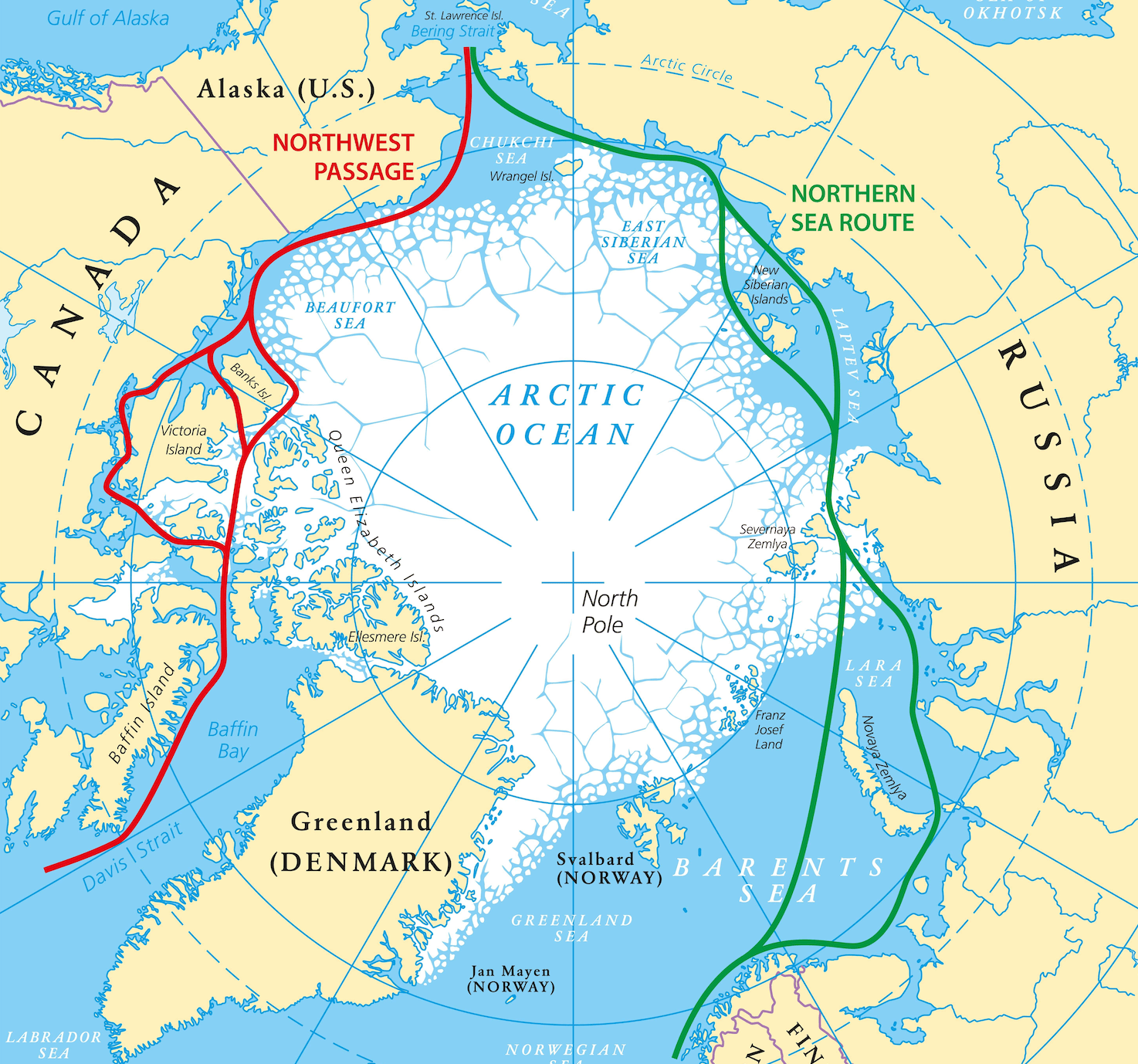

If we analyze the North Sea route along the coast of the Russian Federation, it is up to 40% shorter than the traditional routes through the Suez Canal or the Strait of Malacca. This shortening of the distance means, first of all, savings in time and fuel, which could lower the prices of transported products, but secondly, it would be a great uncertainty because Arctic routes would depend on the vagaries of the weather. The periods of the year when Arctic routes could be navigable are limited, and the supporting infrastructure—ports, icebreakers, rescue centers—is currently underdeveloped. However, there are pilot projects, such as the one recently carried out by China with the Istanbul Bridge ship, which show us that the major economies are seriously testing this maritime transport option. A possible permanent navigation in the future could transform the Arctic into a strategic corridor for trade.

The European Union and its dependence on goods from China

Amidst all the madness of the tariffs imposed by the US on countries around the world, the European Union and China remain key trading partners. It is well known that approximately 20% of the EU’s total imports of goods come from China. This dependence manifests itself in key industries such as technology and electronics, textiles, and pharmaceuticals. In economic terms, almost a fifth of the EU’s economic needs are directly supplied by trade flows from China. This creates a relationship of interdependence, in which the old continent needs Chinese products and China needs the European market for its exports.

The main products imported by European countries from China

The products that European countries import from China are extremely varied and can be grouped into 20 main categories: electronics and IT equipment, mobile phones, computers, solar panels, lithium-ion batteries, electric cars, textiles and clothing, footwear, toys, furniture, medical equipment, pharmaceuticals, household appliances, industrial tools, cables and electrical equipment, electric bicycles and scooters, watches and jewelry, basic chemicals, construction materials, and other consumer goods. Each of these categories fuels value chains that are critical to the European economy.

European industries dependent on China include the automotive sector (especially for batteries and electronic components), the renewable energy industry (solar panels and wind turbines with parts manufactured in China at much lower costs than those manufactured in Europe), the textile industry, mass retail, but also healthcare, where many medical devices and active substances for medicines are imported. This dependence should raise questions about economic security for leaders in Brussels. The most telling example is what we all went through during the COVID-19 pandemic, when European supply chains were massively disrupted.

If we look analytically at the trade routes between China and Europe, by sea and air, we see that maritime freight transport remains dominant, with approximately 90% of goods transported arriving in Europe. The main routes include the route through the Strait of Malacca (the gateway connecting Asia and the Western world) and the Indian Ocean to the Suez Canal, and the Pacific route to the west coast of Europe via the Panama Canal. Air transport, although much more expensive, is essential for high-value, low-volume products such as electronics. Airlines use corridors through Central Asia and the Middle East, connecting hubs such as Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen to European airports such as Frankfurt, Paris, and Amsterdam.

From the perspective of the difference in transport costs and logistics infrastructure between maritime and air transport, we can say that there is a radical difference. According to international transport operators, a shipping container transported from China to Europe costs up to 5-10 times less than one transported by air. The difference is that air transport guarantees delivery in a few days, compared to several weeks or even more by sea. However, the increasingly acute crisis in the Middle East, as well as the incident that led to the blockage of the Suez Canal in 2021, have highlighted the fragility of logistics and led to explosive increases in maritime transport tariffs, putting pressure on supply chains. The Suez Canal plays an essential role in European trade flows. Approximately 12-15% of world trade passes through the Suez Canal, and for Europe, this percentage is much higher. Experts estimate that approximately 40-50% of the EU’s maritime imports transit the Suez Canal, making it a truly strategic point. The main ports of destination for Chinese imports are Rotterdam, Hamburg, Antwerp, and Marseille. The week-long blockage of the Suez Canal in 2021 caused billions in losses, once again highlighting Europe’s critical dependence on this maritime artery.

Countries capable of operating on the Northern Sea Route

Globally, there are only a few countries capable of operating on the Northern Sea Route. This Arctic route requires specialized maritime fleets. Currently, there are only a few countries that have the necessary capabilities. In first place is the Russian Federation, which has the largest fleet of icebreakers in the world, followed by the United States, Canada, and Norway. Although China currently ranks last in terms of the size of its icebreaker fleet, the Asian country is investing heavily in adapted ships capable of handling the Arctic route. The European Union, through Finland and Sweden, contributes with technology and shipbuilding, but the number of ships capable of regular commercial crossings remains limited.

The environmental risks and challenges of the Arctic route

First and foremost, Arctic shipping increases the risk of pollution. The heavy fuels used by shipping vessels have devastating effects on ice and ecosystems. In addition, any accident (which could lead to fuel spills into the sea) would be almost impossible to manage given the current port infrastructure, and climate change is turning the region into an extremely vulnerable area where any incident could have irreversible consequences.

On the other hand, we should look at “The New Golden Road – Europe to India,” a map representing a complex system of trade corridors. These trade corridors connect the port of Trieste in Italy with multiple European and Asian destinations, reaching as far as India. This map highlights the importance of traditional routes through the Suez Canal and the Middle East, but also the increased competition for route diversification, especially by land. Compared to the Arctic option, “The New Golden Road – Europe to India” shows that European leaders are not sticking to a single solution (the Suez Canal) but are looking for a network of complementary routes that will reduce the final cost of products reaching the European market as much as possible. In terms of global freight transport, the future will be defined by the balance between economic efficiency, geopolitical security, and environmental sustainability. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, the Arctic route represents an opportunity, but also a risk. As long as Europe is caught between its dependence on imports from China and the vulnerability of traditional routes, strategies need to be developed to diversify freight transport. It is not only the distance traveled that matters, but also resilience, safety, and impact on the planet. The routes of the future will reflect not only market logic, but also the moral and ecological imperatives of the times we live in today.

Subscribe

Subscribe